South Africa and Malawi: Translocal confinement

Who leaves Malawi? How do they survive South Africa? and how are they experiencing translocal confinement across Lilongwe and Cape Town?

These are questions the ZA-MAL team will explore.

For more than a century, Malawians have migrated in their thousands to South Africa. Translocal bonds have been created, disrupted, and reconfigured in relation to social transformations. Translocal links have diversified over time from originally centering around the industrial heartland of metropolitan Johannesburg, to now also including Cape Town’s squatter camps.

Here, Malawian migrants find themselves in extortionate relations with gangs and residents, confined to cramped living spaces and precarious parts of the labour market. They are faced with oppressive policing relations under threat of detention and deportation. At the same time, many Malawians manage to establish a life and future for their children in Cape Town. It is these simultaneous and contradictory stories of confinement and hope that we will unearth by exploring translocal kin and family relations across Cape Town, South Africa and Lilongwe, Malawi. We seek answer to the following questions:

- What are the memories and experiences of confinement – due to economic marginalisation, stuckness, incarceration, and forced displacement – across Lilongwe and Cape Town?

- How is confinement experienced and perceived across lines of gender and generation?

- Which infrastructures of migration exist to enable or prevent movement – as migration routes have become increasingly arduous, dangerous, and expensive for migrants to South Africa?

The ZA-MAL team comprises three researchers: Daphne Langwe, Shannon Morreira, and Steffen Jensen.

Migrant experiences in townships by Steffen Jensen

I have worked in a Cape Town squatter camp for years and have wondered about the increasing number of Malawians. They live in and alongside the multiple crises that beset Cape Town townships – gang wars, political protests, land invasions, crumbling infrastructure – as well as their precarious relations to neighbors and landlords, gang structures of governance, policing and employers.

I first became aware of the importance of confinement when my friend Mitch told me the following in 2018:

“There is no right for us here [in Cape Town]. You feel like you are in prison. See this phone. It is mine. I bought it. But I cannot use it openly. Someone will come and take it away. If I refuse, they can take my life. I got money but I cannot count it. I have to be in private to count it. I cannot work at night. By 6 o’clock I have to be in my house. Like a chicken, like a cow. Maybe it is worse than prison because a prisoner at least knows what will happen.”

I want to find out how my interlocutors survive and prosper, and which part their family and kinship relations play. This will help us understand issues around confinement on a conceptual level. I will reconnect with friends and acquaintances while paying added attention to their networks back home, and I really want to go with them and spend time in Malawi.

Malawian children and childhoods in Cape Town by Shannon Morreira

In the past, migration between Malawi and South Africa mostly involved men. Men would travel to South Africa for work, while grandmothers, mothers and children usually stayed behind in Malawi. Families were therefore split across countries, and money was sent home to support those left behind.

Today, that pattern is beginning to shift. More families are moving together, with men, women, and children from Malawi now living together in Cape Town. Many of these families face extremely difficult living conditions, with limited opportunities and little ability to move beyond the neighborhoods where they settle.

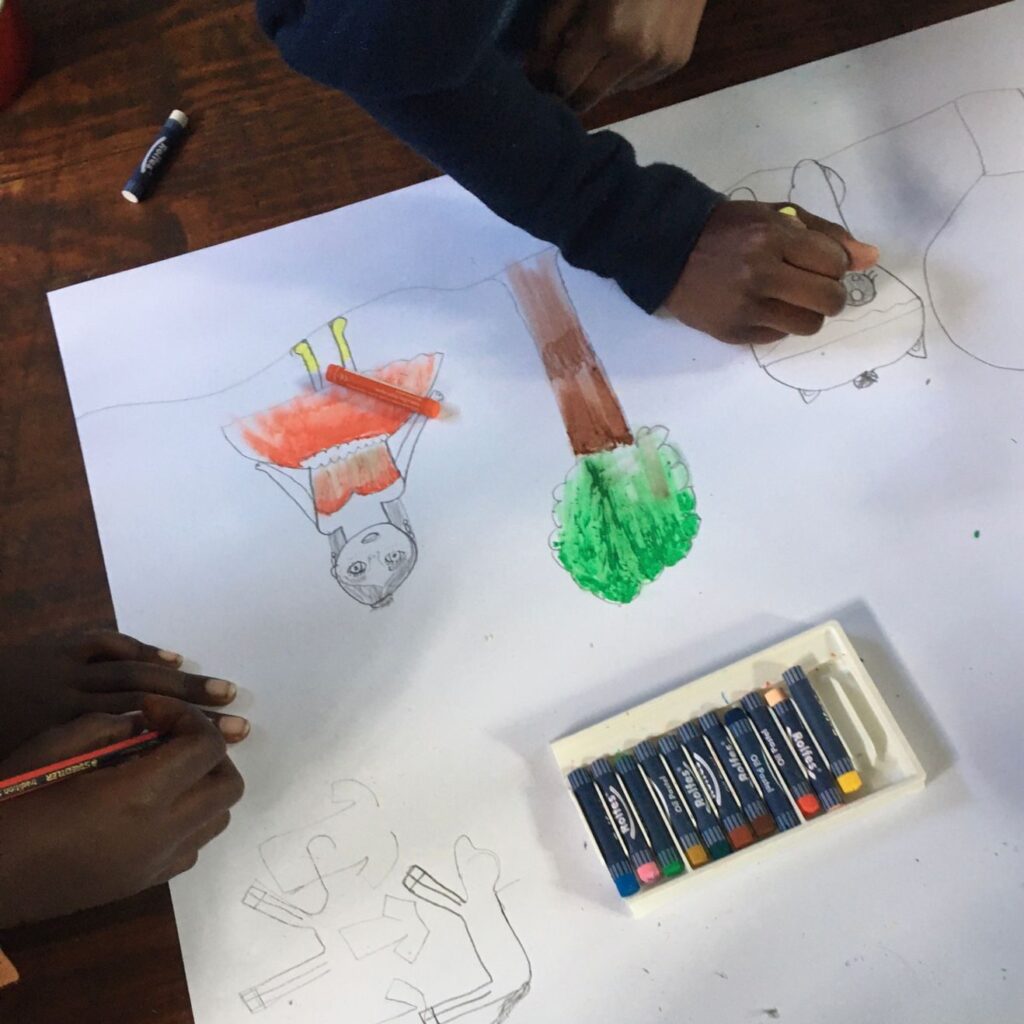

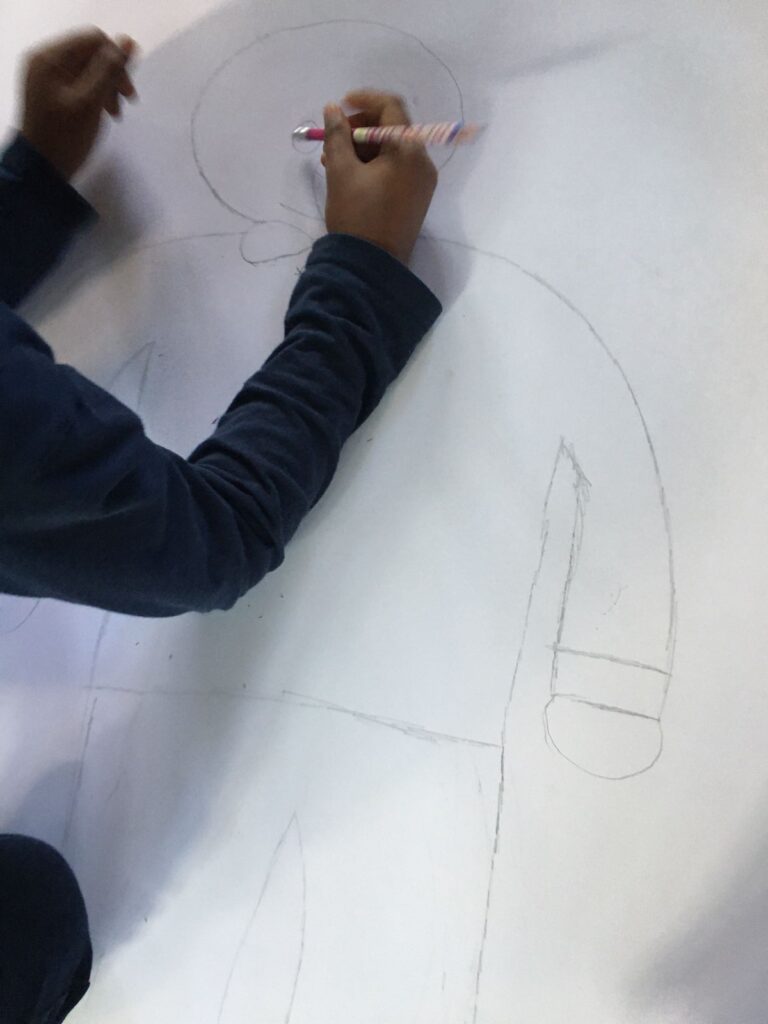

In this part of the wider ZA-MAL project, I focus on these children’s experiences. I will talk, draw and play with children in schools in Cape Town, using participatory art and storytelling methods to explore their understandings of our shared world.

This way we can explore children’s views, as we work together to theorise confinement within the context of mobility.

PhD Project By Daphne Langwe :

Ndende Yosaoneka: The Paradox of Economic Opportunity and Confinement Among Malawian Labor Migrant Families in Cape Town

I grew up alongside and surrounded by Malawi-South Africa migration experiences. The awareness and perspectives of Malawi-South Africa labor migration is one that changes with age and time. It is one that wraps up economic opportunity, mobility, and situations of confinement that come along with it although the latter is less spoken about and to some extent lacks the vocabulary to describe and explain it.

For many Malawian families, migration has meant not only the opening of borders and possibilities, but also the closing down of freedoms in everyday life. This migration creates and affirms different forms of confinement among family members including economic and digital confinement, but also confinement of dreams and aspirations.

For some families, these cycles of confinement affect several generations in a family as children, relatives, and grandparents are pulled in to ‘help’ and support.

So, although the Malawi-South Africa labor migration has historically been predominantly undertaken by men – women and entire families now also undertake the journey. Studying Malawian labor migrants in South Africa therefore necessitates studying the whole family. Not only to examine migration as mobility, but also to confront the ways in which movement produces immobility.

Confinement here is not a single condition but a constellation of overlapping economic, social, digital and spiritual restrictions that shape the everyday lives of families stretched between Malawi and South Africa. Confinement is something that individual family members experience and negotiate differently, but also together as families across borders, within walls, and in the presence of both opportunity and dangers.

This part of the larger ZA-MAL project will examine how Malawian labor migrants experience, negotiate, and understand confinement – both as a family and individually – within different social context either within or across borders. To achieve this, the following research questions will be explored:

- How is confinement experienced by different family members through work, borders, and household responsibilities?

- What are the structures that maintain, reproduce, and manage cycles of confinement?

- What forms of everyday resistance or adaptation do families employ to counter social and economic restrictions?